Gödel Incompleteness THEORY

Kurt Gödel - Vienna 1906 04 28 14 01 1978 Princeton - 1931 ¨uber formal unentscheidbare S¨atze der Principia Mathematica und verwandter Systeme I [On formally undecidable propositions of Principia Mathematica and related systems I].

- If it were possible to define truth in the system itself, we would have something like the liar paradox, showing the system to be inconsistent.

- (Thm) A recursive theory of arithmetic is either inconsistent or incomplete.

- Consistent system cannot prove its own consistency.

Statement

- FIRST INCOMPLETENESS THEOREM. If T is a formal theory containing arithmetic, then it has a sentence which asserts its own unprovability and is such that

- If T is consistent, then T cannot prove the sentence,

- If T is w-consistent, then T cannot prove the negation of the sentence.

- SECOND INCOMPLETENESS THEOREM. If T is a consistent formal theory containing arithmetic, then T cannot prove the sentence asserting the consistency of T.

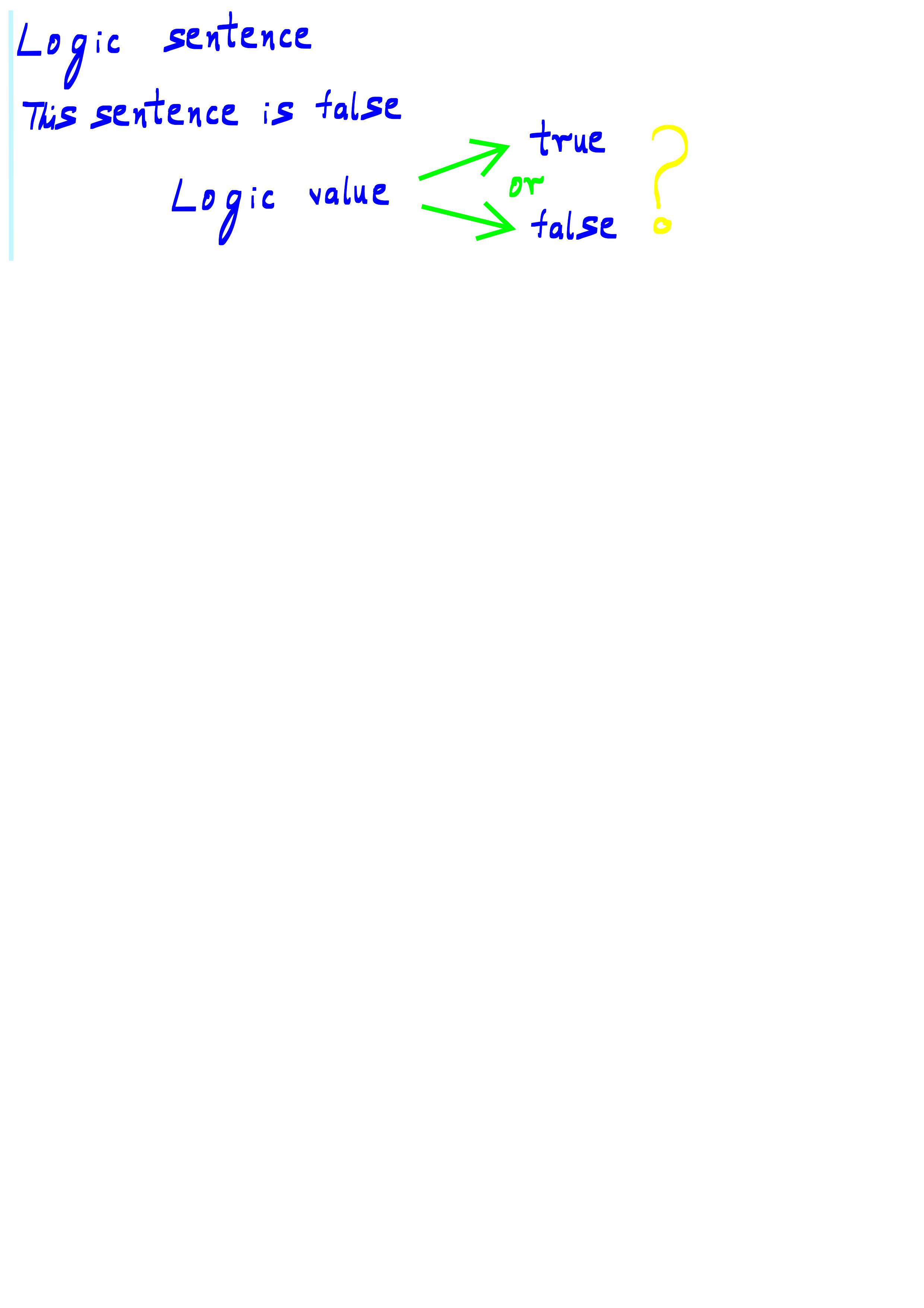

Liar Paradox

The statement mentioned in the first incompleteness theorem comes from arithmetization of syntax to encode the assertion “I cannot be proved”. “I” in the assertion of the statement is self reference to the statement. This is syntactically analogous to the Liar Paradox cited by Gödel. The Liar paradox is:

- Consider the statement “This statement is not true”.

- If statement is assumed to be true,

- Then it asserts that it is not true.

- If statement is assumed to be false,

- Then its negation asserts that it is true.

- Both of the above give a contradiction.

- If statement is assumed to be true,

Gödel then noticed that such a paradox would not necessarily arise if truth were replaced by provability: arithmetic truth and arithmetic provability are not co-extensive.

Syntax

The Language used to describe Liar Paradox can be compactified as follows:

- A part of the statement refers to the whole statement.

- Another part of the statement asserts negation of a property.

Let us try to enocde the statement in Liar Paradox using minimum symbols.

- For the negation of a property, let negation be denoted by \(\neg\) and property be denoted by \(P\).

- Given that \(\neg P\) is a part of the statement, the other part must contain this in order to self refer to the whole sentence.

- Candidate statement: \(\neg P \neg P\) does not refer to itself because even though there is self similarity in between the two parts, there is no part of the statement which refers to the whole statement.

- By defining a contraction of the two self-similar parts, we can have one of the parts recover the whole statement. Let the inverse of this operation be denoted by the mirror reflection symbol: \(\vert\). Operationally the input to the mirror operator is reflected out: \(\vert X = X \vert X\).

- Note that the candidate statement \(\neg P \square \neg P\) must be constrained to preserve this self similarity and also be minimal: any asymmetric statement of the form \(\neg P X Y \neg P\) would not work since one part must contain the other for self reference and any asymmetry in the larger part can be removed to keep it minimal.

- Minimal statement: \(\neg P \vert \neg P\)

- Asserts \(\vert \neg P\) is \(\neg P\).

- By mirror operation: \(\neg P \vert \neg P\) is \(\neg P\).

- Asserts “This statment is \(\neg P\)”.

Application

Jeff Paris and Leo Harrington (1977) showed that the strengthened finite Ramsey theorem is unprovable in Peano arithmetic by showing that in Peano arithmetic it implies the consistency of Peano arithmetic itself.

R

- G¨odel, Kurt. 1929. Uber die Vollst¨andigkeit des Logikkalk¨uls [On the completeness of the calculus of logic]. Dissertation, Universit¨at Wien.